The Non-Equilibrium Physics of Colloidal Sedimentation

Illustration by Enrico Lattuada

Illustration by Enrico LattuadaAlbert Einstein, the father of relativity, was also the hero of another great scientific discovery: Brownian motion. The latter is the disordered motion of small particles - even smaller than a hundredth of the diameter of a hair - inside a liquid such as water. Thanks to Einstein and his contemporaries, we now know that these particles are bumped incessantly by the molecules of the liquid, and it is because of these molecular bumps that they move in a seemingly random way on a larger scale.

One of the crucial experiments for the confirmation of this molecular hypothesis was carried out by Jean Perrin, who understood that these molecular collisions would be strong enough to avoid the accumulation of the particles all at the bottom of a container, but rather would cause a more continuous distribution with more particles at the bottom and a decreasing yet non negligible number when moving up in the rest of the container. This is the so-called sedimentation profile, for the measurement of which Perrin was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1926.

During the formation of the profile, each particle moves in a mesmerizing, and seemingly random way, for two reasons: the first one is Brownian motion, and the second one is the fact that the motion of one particle influences the motion of another particle since they are in the same liquid. This latter effect is clearly visible in a suddenly flipped snow globe, where each particle wanders and changes its direction until it finally reaches the bottom of the globe.

Despite the interest and the extensive investigation performed over the last century, we still do not know how to explain and control the fluctuations occurring during the formation of the profile. Gaining this knowledge would be important for fundamental reasons, as well as for applications, sedimentation being a very common process spontaneously occurring in the natural environment and widely exploited in many industrial applications, such as water purification or wine production.

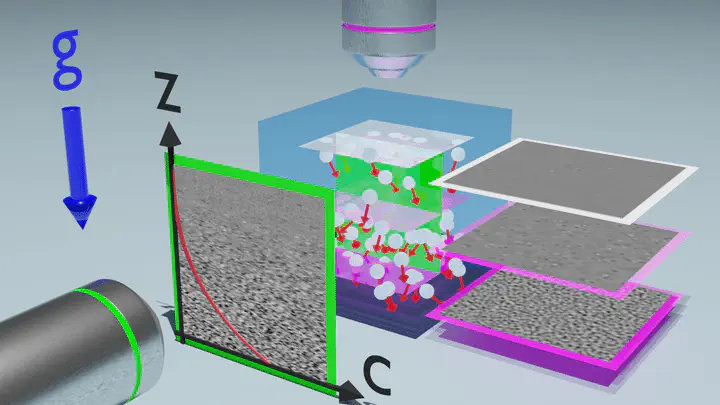

In this project, by walking in the footsteps of Einstein and Perrin, we will combine novel quantitative microscopy approaches and advanced computer simulations to capture in full detail the richness of the sedimentation process in model samples that will be suitably produced in our laboratory. The key idea of our experiments is to combine the classical lateral observations of the sample with observations “from above”. Our expectation, based on previous theoretical work, is that this new observation geometry will provide the missing piece to the understanding of the fluctuations occurring during sedimentation. Beyond answering fundamental outstanding questions, our project will make available novel optical tools for academic research and industry.

Some of our experiments will also be performed onboard the International Space Station, where we will be able to perform our studies in microgravity as well as in controlled artificial gravity conditions.